“One day everything was fine. The next day hell was unleashed.“

“By October 1923, 1% of government income came from taxes and 99% from the creation of new money.”

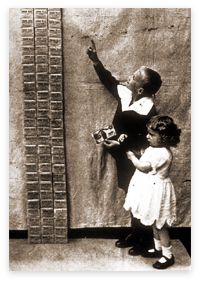

The German inflation of 1923 — one dollar worth trillions of marks.

The German inflation of 1923 — one dollar worth trillions of marks.

If the G8 leaders have shifted from a philosophy of “austerity” to to pursue an acceptance of “inflation,” there are those who suggest that history is a window into the future. Some suggest that the hyper-inflation of post-war Germany in 1922 is a learning post. Some suggest looking at more recent events in Argentina.

“Inflation and the collapse of the exchange are children of the same parent: the impossibility of paying the tributes imposed on us. The problem of restoring the circulation is not a technical or banking problem; it is, in the last analysis, the problem of the equilibrium between the burden and the capacity of the German economy for supporting this burden.”

To get a clearer picture about the period of hyper-inflation in Germany, here are some resources about that period:

- “For reasons that were numerous and complex, economic recovery did not materialize in Germany after the end of World War I in November 1918. Certainly, political instability in Germany was a major factor. In addition, it proved difficult to restore traditional trade patterns.”Some partners and competitors, like the United States, had benefited from the wartime absence of the Germans on the international market. Quite generally, Germany’s trading partners protected their home markets with tariff legislation, and the Reich inadvertently encouraged such retaliation by shortsightedly engaging in large-scale dumping practices.”The low value of the mark made German exports relatively cheap, but this advantage was more than offset by the rapidly rising cost of raw materials and foodstuffs upon which the German economy remained heavily dependent. The country’s economic difficulties can be readily gauged by the mark’s declining value relative to the dollar, the strongest postwar currency: from January 1919 to January 1922, the value of the mark fell from 8.9 to the dollar to 191.8.” (SOURCE: The German Hyperinflation of 1923: A Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Retrospective, Missouri Western University)

- “The German inflation of 1914–1923 had an inconspicuous beginning, a creeping rate of one to two percent. On the first day of the war, the German Reichsbank, like the other central banks of the belligerent powers, suspended redeemability of its notes in order to prevent a run on its gold reserves.“Like all the other banks, it offered assistance to the central government in financing the war effort. Since taxes are always unpopular, the German government preferred to borrow the needed amounts of money rather than raise its taxes substantially. To this end it was readily assisted by the Reichsbank, which discounted most treasury obligations.“A growing percentage of government debt thus found its way into the vaults of the central bank and an equivalent amount of printing press money into people’s cash holdings. In short, the central bank was monetizing the growing government debt.” (SOURCE: Hyperinflation in Germany, 1914-1923, Ludwig von Mieses Institute)

- “Before World War I Germany was a prosperous country, with a gold-backed currency, expanding industry, and world leadership in optics, chemicals, and machinery. The German Mark, the British shilling, the French franc, and the Italian lira all had about equal value, and all were exchanged four or five to the dollar. That was in 1914. In 1923, at the most fevered moment of the German hyperinflation, the exchange rate between the dollar and the Mark was one trillion Marks to one dollar, and a wheelbarrow full of money would not even buy a newspaper. Most Germans were taken by surprise by the financial tornado.”‘My father was a lawyer,’ says Walter Levy, an internationally known German-born oil consultant in New York, ‘and he had taken out an insurance policy in 1903, and every month he had made the payments faithfully. It was a 20-year policy, and when it came due, he cashed it in and bought a single loaf of bread.’ The Berlin publisher Leopold Ullstein wrote that an American visitor tipped their cook one dollar. The family convened, and it was decided that a trust fund should be set up in a Berlin bank with the cook as beneficiary, the bank to administer and invest the dollar.“In retrospect, you can trace the steps to hyperinflation, but some of the reasons remain cloudy. Germany abandoned the gold backing of its currency in 1914. The war was expected to be short, so it was financed by government borrowing, not by savings and taxation. In Germany prices doubled between 1914 and 1919.“After four disastrous years Germany had lost the war. Under the Treaty of Versailles it was forced to make a reparations payment in gold-backed Marks, and it was due to lose part of the production of the Ruhr and of the province of Upper Silesia. The Weimar Republic was politically fragile.

“But the bourgeois habits were very strong. Ordinary citizens worked at their jobs, sent their children to school and worried about their grades, maneuvered for promotions and rejoiced when they got them, and generally expected things to get better. But the prices that had doubled from 1914 to 1919 doubled again during just five months in 1922. Milk went from 7 Marks per liter to 16; beer from 5.6 to 18. There were complaints about the high cost of living. Professors and civil servants complained of getting squeezed. Factory workers pressed for wage increases. An underground economy developed, aided by a desire to beat the tax collector.” (SOURCE: The German Hyperinflation, 1923, PBS.org)

- “If history teaches anything, it is that government cannot be trustedto manage money. When currency is not redeemable in gold, its value depends entirely on the judgment and the conscience of the politicians.”Especially in an economic crisis or a war, the pressure to inflate becomes overwhelming. Any alternative may seem politically disastrous. Whether it be the Roman emperors repeatedly debasing their coinage, the French revolutionary government printing a flood of assignats, John Law flooding France with debased money, or the Continental Congress issuing money until it was literally “not worth a Continental,” the story is similar.”A government in financial straits finds its easiest recourse is to issue more and more money until the money loses its value. The entire process is accompanied by a barrage of explanations, propaganda and new regulations which hide the true situation from the eyes of most people until they have lost all their savings. In World War I, Germany — like other governments — borrowed heavily to pay its war costs. This led to inflation, but not much more than in the U.S. during the same period. After the war there was a period of stability, but then the inflation resumed. By 1923, the wildest inflation in history was raging. Often prices doubled in a few hours. A wild stampede developed to buy goods and get rid of money. By late 1923 it took 200 billion marks buy a loaf of bread.”Millions of the hard-working, thrifty German people found that their life’s savings would not buy a postage stamp. They were penniless. How could this happen in a highly civilized nation run at the time by intelligent, democratically chosen leaders? What happened to business, to wages and employment? How did some people manage to save their capital while a few speculators made fortunes? (SOURCE: The Nightmare German Inflation. [NOTE: This is an excellent assessment, though the source is a private company dealing in the sales of gold. Columbia news, views & reviews does not recommend any financial product; inclusion of the information is for historical perspective.]